How does Manos Nathan re-define the variety of influences, which he draws on in his pottery in order to maintain a Maori kaupapa?

Manos Nathan graduated from Wellington Polytech principally as a painter. He was conscious that his training drew largely from a Bauhaus ethos as many of the staff came from the Netherlands and realised that he would prefer to somehow mitigate that influence. When he went to Europe on his OE he looked at a lot of art, mainly religious, like Byzantine icons and medieval German woodcarving, that for him, ‘had wairua’. He realised that ‘this is all at home and I have been riding over the top of it’.

He returned and shortly afterward had a call from his family to help with the carving of the Matatina Marae at Waipoua, Northland. This realisation that his centre lay with his Maori heritage seemed to him important knowledge to take to this task. While he had no formal training as a wood carver, he knew how to use hands and eyes, and with that he then attended another school, just by working with the elders on his marae. One knowledgeable elder, Maori Marsden, was ‘a man of both worlds with degrees in anthropology and divinity, had a huge influence on how to perceive things Maori’. He was Nathan’s mentor, teacher and guide. As they worked together, Nathan was taken deeper into what Maori art is, and was, and what its role might be today.[1]

Clay as a medium was not considered at all at this stage but came into the picture some years later through the instigation of Doug Chowns from the Northland Community College. He proposed that Nathan come and view Robin Stewart teaching. Nathan says that at this point he was simply an observer, having taken some time out from carving the Marae, while Stewart suggests that he was a co-teacher who was explaining about the application of Maori designs to pots. We can imagine that something of both probably occurred in the ambience of a summer school in Northland. It is doubtful that anything of a formal atmosphere prevailed, and that a free exchange of information took place. Stewart was at that stage applying Maori imagery to pots, and felt that she had the co-operation of Alec Musha and Toi Maihi with this. She told Nathan of the whakapapa of the technique, as far as she was concerned, which was with Maria Martinez and the pueblo Indians of Arizona and New Mexico in the USA.

Martinez had re-discovered methods for producing blackwares using evidence from shards found near her village on the Hopi Reservation. The resultant pots were much sought after and Martinez became well-known. The economy of her Pueblo was changed, and pottery, until then considered a dying tradition of Native American women, revived and has many practitioners, male and female, today.

What Nathan saw was a low-tech method perfectly suited to the sort of initiatives that might be implemented at places like Matatina at Waipoua, capitalising on local resources. They had the clay, and river sand as a tempering agent, and plenty of dung. It was introduced as an adjunct to other endeavours undertaken at Waipoua, as people were returning to the papakaianga. It offered a craft with multiple purposes; a source of slowing down—as hand-built pots take time; a means of connecting the makers with some aspects of their heritage, and a safe way to keep hands busy. The students were often ‘street kids’ that had been repatriated North, and ‘…no way was I going to give them chisels and adzes!’ Nathan saw it as ‘good therapy’ and ‘a filter’ to sort out the young people with promise, and ‘take them into the woods.’ Nathan asked Stewart to come to the marae and teach which she did on a couple of occasions, and both remark that at that time she learned as much as she taught.

Stewart considers Nathan’s early pots to be probably the best she has seen. He progressed swiftly and could apply decoration intelligently, advancing from simple linear application of design to a complexity of carving into and building up of the surface with an early Waka Whenua for the placenta of one of his children. A natural dexterity is evident and his carving experience and design school training feeds into this.

In 1984, Nathan’s father had gone to the USA as a member of one of the parties that accompanied the Te Maori exhibition. He brought back books on the south-west area and one on the work of Martinez, containing sequential pictures showing method. Nathan, working from the basis that Stewart had provided, then followed what he interpreted from those photos and developed his work.

Nathan and Baye Riddell, a Maori potter from the Gisborne area (Ngati Porou) in 1989 received a Fulbright Cultural Grant to go to the USA and investigate the sources of the work that interested them, and meet the makers—indigenous people with a long ceramic tradition. They went to the mesas on the Hopi tribal lands, and to the Santa Clara and San Ildefonso pueblos. They became aware of huge differences with the cultures, but found similarities with ‘heart and head space’, and made a connection. There was interesting korero (exchange of views) with discovering correspondences and paradoxes in design features and the profound differences with clays from a geologically old land compared to Aotearoa. They went then to Washington and ‘knocked on doors’ to bring about a reciprocal visit. Witi Ihimaera was there, working at the New Zealand Embassy, and proved helpful. In 1992, with the help of Fulbright, Te Waka Toi and the Waewae Tapu scheme for distinguished guests, there was a visit from a group of Hopi and Pueblo potters. The group visited Tokomaru Bay, Coromandel and Waipoua. There was again intriguing korero as the audiences, mostly Maori, observed the Indian reverence and care for their materials—their clay is hard-won and laboriously worked prior to pot making, and Pueblo Indians keep their sources of clay and minerals a secret, and within a family. Potters here can easily buy ready-prepared clay and so treat it casually. The Native Americans were surprised at the free sharing of information between the New Zealand potters from different areas. The primary concern was the experience and gaining a body of knowledge to share.

As the work with clay began to absorb more of his time and energies, Nathan was challenged by his elders, ‘particularly my old aunties’, to justify his actions. He felt at first that they would prefer him to stay in the ‘comfort zone of wood carving’, but on later reflection he realises it as a subtle way to direct him to move deeper in to links with Maori traditions. When carving, nohopuku (to sit inside yourself/meditate) must be part of the process. He realised that he must make those connections for his processes, in order for what he was doing to be accepted.

Maori cosmological/creation stories provide a rich heritage and Nathan realised that the key was to connect with those allegories and metaphors. There is whakapapa for clay, sand, water and fire, (all necessary elements for the processes of ceramics) and they gave him a cultural template—a foundation and springboard from which to reinterpret and develop an identity for the non-customary medium of clay.

For example, Nathan says that most Maori link fire with the Goddess Mahuika, and the securing of fire for humanity by Maui, but that it goes further back than that. The origin lies with the primal parents, Papatuanuku and Ranginui, and when they were separated, the children took the fire making tools that were suspended around Ranginui’s neck, and Tane used the tools to generate the first fire, the sun. This was also the origin of the falling of fire, (Ahi Komau). Sparks that fell became the potentiality for fire in certain woods used for its creation. Nathan also links the separation of the primal parents and the resultant bleeding with kokowai, the red ochre used in colouring clay.

By linking his processes with this nexus of narratives, Nathan gained approval for his work from his whanau. He sees it as ‘a beautiful, gentle way of teaching.’ In his efforts to create an identity and profile for works in clay by Maori, he adapted design and symbolism from the customary art forms of wood, stone and bone carving, from ta moko and from the fibre arts of taniko and tukutuku. He embellished some early pots with inlaid paua and bone and ornamented with muka and feathers. His intent has been to forge a link with Maori custom and traditional values and to make works in clay accessible and acceptable to Maori.

His earliest works that specifically fitted in to a Maori cultural context were vessels for the reception of the placenta and umbilical cord (Waka Taurahere Tangata and Waka Pito). These clay pots linked to traditional rituals, and via their burial, to the acknowledgment of genealogical affinities with the land.[2] The aesthetics of custom were addressed with his Ipu Pure—replacement for the plastic bottles and bowls in use for cleansing rites at urupa (cemeteries) throughout the north.

He sees himself and his contemporaries, the other members of the Maori clay workers’ group (Nga Kaihanga Uku), as being ‘in missionary mode, promoting clay as a viable option, laying foundations, so the young can spring off. We can apply our own logic and connectors—our own frames of reference, the meaning is ours.’ Nathan is pleased to have done this and makes no attempt to guess where it might go.

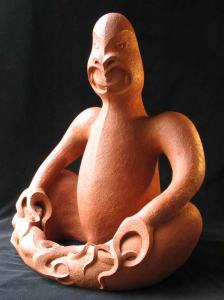

The focus for his new work is found in Northland, specifically taonga of the Northern carving tradition, the funerary chests (Waka Koiwi ) of Tai Tokerau. These ossuaries, holding the bones of ancestors, were looted from burial caves in the early twentieth century and were the subject of one set of submissions to the Waitangi Tribunal, with which Nathan is involved. Some bones were returned in the late eighties, but not the chests. They remain, as part of the Turnbull and the Spencer collections, in museums to the south and off-shore. Whakapakoko is the old generic word for these chests, and means ‘dried up and mummified’, but the translation was usurped to mean ‘graven image’ by the missionaries and as such was associated with idolatry, thus encouraging the removal of the chests. ‘These carvings are not idols, but books, and they are specifically ours.’ The neat connection to books links with what Nicholas Thomas says about ‘Maori face their ancestors rather than the future…because genealogy and ancestral presences were sources of empowerment in the present.’[3]

The chests have characteristically forward leaning heads and a wide body with a keel line, which, in terms of Maori symbology is a mnemonic for whakapapa again, the same principle as with a carved house where the ridge pole can mean a tree trunk or the backbone of an ancestor. The names change with the symbol. Nathan raises these matters, which are not in the public domain due to the sensitive and tapu nature of the taonga, through his art. The underpinning issue being the repatriation of taonga.

From this base, Nathan plays with the elements of form to explore the sculptural potential of these works. Rather like the prow of a canoe or the figurehead of a ship these forms lean forward eagerly, as if to progress the journey. Indeed, considering their derivation they could be hastening toward an afterlife. The river flowing below Matatina marae is the Waipoua, but metaphorical links to the Styx are not difficult if one broadens the cultural context.

The works also carry a distillation of quietude; there is little animation or expression. While lines flow, it is the meander of a rivulet on flat land rather than the energetic turbulence of water through a ravine. They do not transgress space; do not carry the eye beyond their perimeters. Instead, the control means they are enclosed by it; wrapped up and contained. In a sense, much as their exemplars did for the bones they once embraced.

Some pieces have open mouths, which resonate both traditional figurative carving and perhaps an anguished cry, a waiata of loss. The whakapakoko, their issues and aesthetics, have been incorporated by Nathan; they are a part of what he is, and does.

He has moved a long way from the early correspondences with the pots of American First Nation peoples. Former hybrid work shows an adaptation of form from Native American pieces with Maori surface decoration, and demonstrated considerable technical dexterity and intelligence. His work has now moved into a realm that is categorically entirely Maori. It still retains a feel of being carved rather than a manifestation of working with a malleable medium. However, contemporary opinions are that clay can be used for its ability to imitate any other material and not just its plastic properties, which has been the prevailing, modernist, view. Furthermore, Nathan’s background of traditional carving will probably always be with him.

Nathan has transferred his rationale to a basis within his Maori heritage and his work towards a more local expression. His was a starting point in another culture but he has no need of any further borrowing, despite ample precedents. Jenny Pattrick has said, ‘Maori artists are, I think, more inclined to borrow whatever tools or skills they need from other cultures, to express themselves in contemporary ways.’[4] There is some history here, witness the rapid acquisition and use of European tools from early contact. There is also history of cultural borrowing within Polynesia, for example, the Tahitian tattoo patterns are these days derived more from Marquesan sources than from ancient Tahitian practices.[5]

‘Appropriation is the single most characteristic aspect of the art of the twentieth century. the ‘centre’ looking to the ‘periphery’. The word ‘appropriation’ conflates the ideas of property and appropriateness.’ [6]

Nathan learned from a pakeha who had already appropriated American first nations methods for her own reasons and who was careful to discuss what she did with Maori. Nathan’s initiation into these procedures and histories was already second hand. After the inaugural experiments and development, there was a transaction when Riddell and Nathan visited the First Nation Indians in their own territory. Reciprocity by way of a return visit was secured and contact and exchange still take place. There was, and is, no power relationship here. If the exchange is a negotiation between equals then appropriation is not at issue.

The invention of a ‘new tradition’, if that is not a contradiction of terms, means that Nathan, and his fellow Maori clay collective members, can make reference to traditional Maori form and surface, but can also extrapolate upon them as they will. Rangihiroa Panaho talks of ‘the innovative and adaptive nature of Maori culture.always in a state of flux’ and, ‘a tradition of change.’, and a history, ‘of innovative and aggressive Maori adaptations of Pakeha forms, design, technology and materials.’.[7] Nicholas Thomas mentions an ‘energetic motion of Maori art…transpositions across artefact types and media…as though motifs had a capacity to replicate themselves on different materials and in different contexts’.[8] There are ample precedents of exchange travelling in both directions, from within and outside of the culture.

There are no Maori archetypes that must be followed for clay. The artists can utilise elements, as they deem appropriate, without the requirement to follow a particular path. However, in another sense, this first generation’s pieces are founded in customs and, careful of acceptance for the medium, they are unlikely to move too far away from a strong link with Maori culture.

Nathan could delve into his Mediterranean ancestry. His mother was from Crete—a war bride, and Manos would not look out of place in a waterfront taverna in Rethymnion. Crete has a rich, 5000 year old, ceramic history of naturalistically decorated earthenware from which to source work. However Nathan is content to mine his Maori heritage at present, finding that sufficient and relevant.

Nathan’s work is political, but not aggressively so. He seeks to negotiate for himself a place as an artist with this new medium and he has done much towards making clay accepted by Maori as a viable medium for Maori expression. He does not challenge boundaries between arenas of art (high and low, male and female, art and craft) as a pakeha ceramist might do. He is uninterested in these sorts of parameters. Instead his politics lie with economic issues for some of his hapu, and a focus upon repatriation issues, of land and taonga. His work does not express this overtly. Instead, it raises the issues-a strategy of subterfuge-through a re-interpretation of Maori cultural forms and surfaces using a non-traditional medium, and drawing from a rich legacy of allegory and metaphor.

NOTE ONE – A potted Pottery History

From earliest times man has valued the plastic qualities of clay. It could be formed by hand into votive figures or used to seal baskets. The history of pottery really starts with man’s realisation that when clay reaches a sufficiently high temperature (and an open fire can just achieve this), the nature of the material changes. It can no longer be softened by water to return it to its plastic state. The earliest pots are believed to have resulted from clay-sealed baskets, placed too close to a fire, resulting in the basket material being destroyed, but a warp and weft patterned pot remaining.

However the fragility of such low-fired pots did not lend themselves to a nomadic life. And the development of pottery began only with the settled agricultural societies of the Neolithic period. The earliest known pottery, from Anatolia (now in Turkey), dates from the seventh millennium BC.

The technique of burnishing, to give a shiny even surface that reduced porosity was progressively developed, and the use of liquid clay ‘slips’, stained with certain mineral colours that could withstand the firing process, thus giving a limited sober range of browns, orange-reds and blacks allowed decoration of wares. Early decoration was geometric, later naturalistic, and examples, from Mesopotamia and Persia, exist today dated from 4000-4500BC. Pre-dynastic Egypt and the Minoan culture of Crete, and later, the Greeks, all produced significant pottery from which we know much of their cultures.[9]

Asiatic cultures also developed pottery traditions from the third millennium BC and made large handsome jars with burnished surfaces, slip decorated with geometric patterns. However, later in Asia, glazes were developed which set their ceramic production into a very different sphere.

A major civilization that developed in complete isolation from the Western and Asiatic traditions was that of pre-Columbian America. Many cultures came and went there, throughout the ages, and due to widespread customs of burying pottery with the dead, there is a rich ceramic legacy. Glazes and the wheel were never invented and so all pottery was handformed, and much was burnished.

With the exception of the pre-Columbian wares of America, most of the world’s ceramic traditions are, to a degree, interrelated. Ceramics seem to cross cultural frontiers readily for while some arts from alien cultures might be incomprehensible, the common language of ceramic forms and functions renders them approachable. Dishes, bowls, vases and ewers (liquid containers) are common to most societies; if the proportions and decorations of a foreign ewer might be strange, its function would be clear, and if proved superior to that of the local wares it would be imitated. From earliest times there was trade between the ancient Mediterranean civilisations and Asia, along the caravan routes of the Middle East. Similar decorations have appeared on Greek, Central Asian and Chinese ceramics, which have then been returned to the West through the Mongol conquest of Persia and Turkey. Islamic metalware has influenced many Chinese forms, which culture also exported its accomplishments. Chinese glaze technology was widely emulated in many countries with which it traded, in Asia and the Middle East, while Islamic techniques added to European traditions. Cross-fertilisation has been endemic within the history of ceramics.[10]

NOTE TWO – Ceramics in New Zealand

In New Zealand, no uses of ceramic developed despite adequate quantities of suitable clays. There is a history of clay vessels from the Lapita culture of Oceania, but this did not arrive in Aotearoa with the early immigrants. Clay use had ceased in many areas of Oceania prior to the migrations to Aotearoa. When early Maori arrived there was a very different lifestyle to establish. A colder climate and entirely different flora and fauna almost certainly gave these early settlers more than sufficient to deal with. The traditional uses that clay vessels might have been applied to were taken over by other media such as wood and gourds, and large scale food storage was catered for by raised food-storage houses (pataka) and pits dug into the ground and covered with timber and foliage.

A clay culture only really flourished in New Zealand post the second World war, when the philosophies of Bernard Leach arrived with the Anglo/Oriental movement. While there was, at least, one early Maori practitioner in Selwyn Wilson, from Northland, who trained as an art teacher under Tovey, and subsequently honed his craft at the Central School in London in the fifties, it was basically a vocation for the educated, white, middle-classes at the time. It flourished until the early eighties when Governmental decree removed import restrictions on ceramic items and the flood of cheap and colourful goods largely destroyed a healthy cottage industry that had supplied kitchen and tableware to an avid public. The craft has continued, in attenuated form with fewer practitioners, with less emphasis on tableware, more on personal expression and the decorative.

NOTE THREE Robyn Stewart

In the mid-seventies, Robyn Stewart was casting around for a means of occupation at the prospect of a move to mid-Northland—to a farm her husband had bought. She went to the Auckland Studio Potters centre for classes in pottery and was taught by Margaret Milne. On the last day they were shown films, one of which was an NZBC documentary of Maria Martinez, a Native American from the San Ildefonso pueblo, New Mexico. The documentary showed Martinez hand building, carving and burnishing her pots, then firing in an open fire and smothering the flames with dung. ‘There will be plenty of that where you’re going Robyn’, was the spur, and Stewart realised that this low-tech means would be perfect for her situation.

Considerable trial and error followed as the film had not been explicit as to methods or technical details. Clay was dug from different parts of the farm, and Stewart experimented with some carving and polishing. There were many failures and most cracked in the primitive firings. Stewart came down to Auckland for a ‘Raku’ workshop. Raku is a Japanese method and philosophy, hundreds of years old, whereby the pots are heated and then cooled rapidly by quenching in cold water. To withstand the thermal shock the clay body is tempered by ‘opening’ with materials such as ground fired ceramic, volcanic ash or sand. This was the information Stewart needed and more empirical work followed, this time more successful and after eighteen months she had six pots to exhibit. It was, at that time, new to New Zealand.

At this point she joined the Northland Society of Arts where she met Alec Musha, a Maori from Coromandel area who was interested in what she was doing. Musha was an accomplished potter, in the Anglo/Oriental style, taught by Yvonne Rust, and Stewart consulted with him about what sort of Maori designs could go on to pots.

Stewart grew up in Orakei, in Auckland, where there is a large urban Maori community and she attended the local primary school with Maori teachers and where there were more than fifty percent Maori students. A child of the Gordon Tovey era, she had learned about Maori culture, art and design while at school, and felt comfortable and familiar with it.

Musha introduced Stewart to Toi Maihi and the two women shared an exhibition, in Whangarei, where Maihi’s images were applied to Stewart’s pots and Maihi hung her screen prints with the pots. The exhibition was received well and the Stewart was invited to exhibit with Maori Artists and Writers through Musha and Maihi. Following this she taught some of her methods at various workshops in Northland. Some years later Douglas Chowns, at Northland Polytechnic, asked her to teach at a summer school. There she met Manos Nathan, a carver of wood and bone at the time, who was ‘a co-teacher in the workshop for the uses of Maori design on pots’. She subsequently went to his Marae in the Waipoua Forrest to teach on several occasions, and was again asked back when the pueblo Native Americans came in 1992. Stewart has shared her skills at workshops at Tairawhiti, Gisborne and at Whanganui Polytechnic where she also taught Wi Taipa. Stewart says her interest has always been, once the technical problems were solved, in ‘a New Zealand expression of clay’. That she saw this as Maori design is obvious from early works. The author has seen Theo Schoon images of Maori rock drawings on the wall of her workshop. However, aware of criticism, she has changed from this policy and now confines her much simplified designs on pots to a spiral form that is non-specific in origin. (Much of the above is transcribed from an interview with Stewart, 16 April, 2001. The remainder is personal observation by the author.)

NOTES FOUR – Maria Martinez.

Maria Martinez often said that she was the most famous Indian, after Geronimo. She was born in the San Ildefonso pueblo in about 1880, there is no accurate record, and died in 1980. She made pots for about eighty-five years. She learned from an early age and showed talent with the traditional polychrome wares of her village. At that time they were in both daily use and sold for small amounts at markets to help economically. She married Julian Martinez in 1904. He was an acknowledged painter on hides, paper and walls, and then on Maria’s clay.

About ten years later, as a skilled potter, she was asked to investigate the techniques needed to reproduce polished black shards (broken pots) unearthed at a nearby archaeological site. After experimentation the first blackwares appeared when they smothered the bonfires containing what would have been red clay pots.

The Martinez continued to refine the techniques for firing and decorating and their black-on-black wares became well known. In early years Maria had sold her pots at the railway station in Albuquerque and in markets in Santa Fe. Once the blackwares were (re)developed, buses brought tourists to the pueblo to see Maria, who was welcoming and gregarious, and the pots were sold from there. This changed the economy of San Ildefonso Pueblo. Prices for Native American pots are now extremely high, in any marketplace. Maria Martinez is matriarch to a long line of potters, no longer exclusively women.

METHOD

The clays are prospected from reservation lands and tempered with volcanic ash, sand or fired clay shards, ground laboriously by hand. Decoration is by painting with pigments made from minerals found as sludge in the deserts or as metallic rocks that must be ground fine and then mixed with water. Sources are often secret, known only to members of a family. The pots are painted with brushes made from yucca, first chewed supple, then shaped and cut with a tool.

Pots are hand built and when almost dried, burnished with a pebble until the pot yields a mirror-like shine, and decorated by brush. To fire they are laid on a layer of sheep dung spread over sand on the ground. The pots are covered with shards or old car number plates found along the roadsides. Finally another layer of dung is spread to cover the whole domed pile. Firing is fast, about an hour or so and the pots are removed hot, with a stick and wiped clean with a cloth. The process is surrounded with traditions and beliefs that are often centuries old.

The above notes are taken from Peterson, Susan. ‘Pottery by American Indian Women – the Legacy of Generations.’. Abbeville, New York. 1998.

[1] All quotes taken from a taped interview with the artist. 7April,2001.

[2] Pricilla Pitts, in Contemporary New Zealand Sculpture, p78, talks of these Waka Pito and Waka Tauhere Tangata, and claims that ‘…eventually both clay pot and body parts will break down and return to the earth from which they originated.’ This indicates a lack of research, although a poetc link, as any ceramic pots can remain for thousands of years. This is the material by which many civilisations are measured and marked.

[3] Thomas, N. Oceanic Art. London, 1995. P60.

[4] Pattrick, J. in Mana Tiriti. Wellington.1991. P56

[5] Thomas, N. in ‘The case of Tattooing.’ In Border Crossings: Contemporary Artists and Anthropology. London 2002. (as yet unpublished paper for the above book.) p.7.

[6] Gill, L. in ‘Gretchen Albrecht’, in Distance Looks Our Way. P36.

[7] Panaho, R. in ‘Maori at the Centre,On the Margins’ in Headlands – Thinking through New Zealand Art. Sydney, 1992. p124

[8] Thomas, N. Oceanic Art. OpCit. P76.

[9] Manners, E. Ceramic Source Book. London, 1990. Pp18-21

[10] Manners. Ibid. Pp10-15.

Moyra Elliot is a New Zealand writer. By Moyra Elliot

Truly Awesome work Manos

Kia ora Tommy…see you @ Kokiri Putahi!

beautiful Manos

Kia ora Basil. Thank you…needs a tweak or two but getting there. The ever patient Andrea will work on the Gallery section …. I would prefer the images to be larger when viewed.

Ps: That was Manos inside my account that answered you before Basil 🙂 – AEH. The new Gallery page is almost complete.